The Human Attention Crisis

When Language Becomes Infinite

We now produce somewhere between 15 and 70 trillion tokens of text every day.

To put that in perspective: GPT-3 was trained on 500 billion tokens. Humanity now generates that volume in less than an hour. At its peak, the Library of Alexandria held 4 billion words. We surpass that in less than 60 seconds.

This isn’t just information overload. It’s something more fundamental: for the first time in human history, the rate at which language is produced has exceeded the rate at which humans can meaningfully process it.

Language is infinite. Attention is finite. And the gap is widening daily.

Why This Matters More Than You Think

Language isn’t just communication. It’s humanity’s foundational technology: older than agriculture, older than writing, older than the wheel.

Yuval Noah Harari describes reality as having three layers: objective reality (physics, independent of belief), subjective reality (your inner experience), and intersubjective reality (shared beliefs that exist because many people agree on them). Money, nations, laws, marriages, corporations: these are linguistic constructs. They have power precisely because they’re collectively imagined and continually reinforced through language.

This intersubjective layer is the operating system of civilization. It’s how strangers cooperate, how institutions persist, how societies cohere.

And it’s exactly what’s under assault.

When language production becomes infinite while attention remains finite, the intersubjective layer destabilizes. Shared reality fragments. Trust erodes. Coordination fails.

This has happened before.

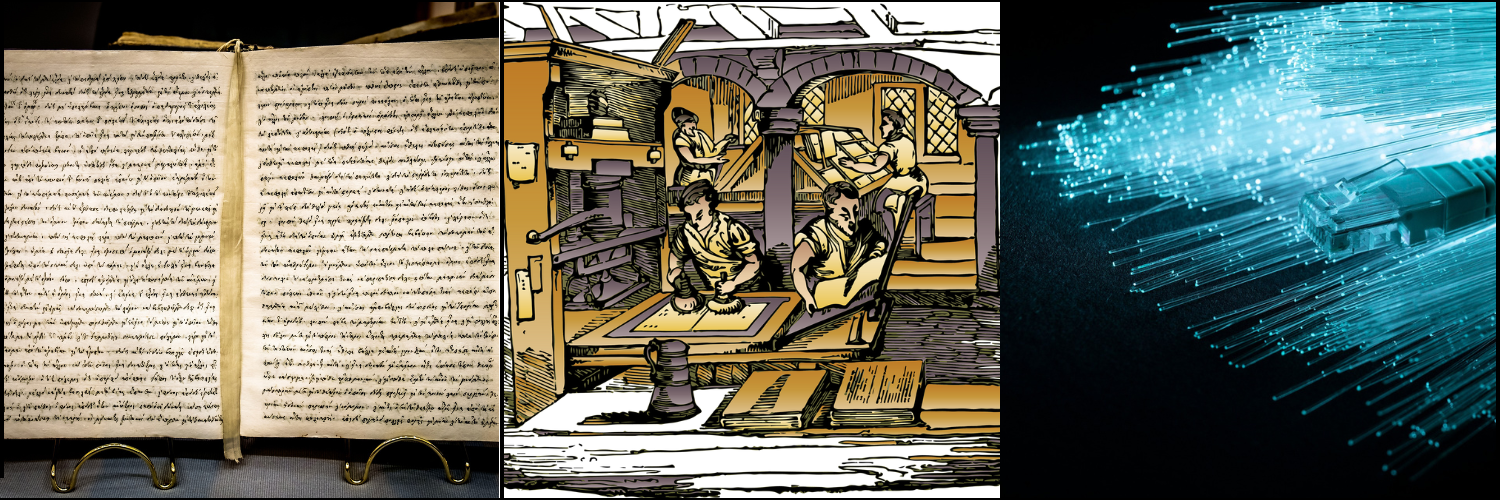

The Pattern Across Centuries

In 1486, an inquisitor named Heinrich Kramer published Malleus Maleficarum, a manual for identifying and prosecuting witches. Before the printing press, such a text would have circulated among a handful of clergy. But Gutenberg’s invention had arrived just decades earlier. The Malleus went through 28 editions, reached tens of thousands of readers, and transformed local superstition into a continent-wide intersubjective reality. The result: 110,000 trials, 40,000 to 60,000 executions, mostly of women, over two centuries.

The printing press didn’t create misogyny or fear of the occult. It amplified them faster than society could adapt.

Five centuries later, the same pattern unfolded in Myanmar.

In 2014, Myanmar had almost no internet penetration. Then SIM card prices collapsed, and tens of millions came online almost overnight. For most users, Facebook was the internet, their sole source of news, community, and identity.

Into this environment flowed coordinated disinformation portraying the Rohingya Muslim minority as an existential threat. Engagement-optimized algorithms amplified the most inflammatory content. A new intersubjective reality formed: the Rohingya were not merely “others” but enemies to be eliminated.

The result was genocide. Over 10,000 killed. Nearly a million displaced. The UN concluded that Facebook played a “determining role.”

The technology didn’t create prejudice. It accelerated narrative formation and emotional contagion beyond the capacity of institutions, or citizens, to resist.

The pattern is consistent across centuries:

- A new language technology emerges

- The cost of producing or distributing language collapses

- Bad actors exploit the new medium

- Institutions lack capacity to filter or regulate the surge

- A manufactured intersubjective reality takes hold

- Violence follows

Today, we face the most extreme acceleration yet. Large language models have collapsed the cost of generating language to nearly zero. A single person with access to a generative model can now produce more text in a day than a medieval monastery produced in a year: tailored, fluent, emotionally optimized, and indistinguishable from human prose.

A Personal Inflection Point

The societal attention crisis mirrors an experience I have had directly.

After a reduction in force ended a career chapter I’d inhabited for decades, my attention collapsed inward. For nearly a year, it narrowed to a single imperative: replace what had been lost. Find job → Restore security → Eliminate uncertainty. It wasn’t a strategy. It was reflex: the predictable response of a mind shaped by fifty years of expectation and fear.

That internal narrative left no space for curiosity, exploration, or reflection.

When those efforts repeatedly failed to materialize, something unexpected happened. I stopped. Not entirely (responsibilities don’t vanish), but enough to notice the pattern. Enough to ask a question I hadn’t allowed myself to ask: What do I actually want to pay attention to?

The landscape didn’t change. But the meaning of the landscape did.

That experience clarified something essential. Just as individuals can drift into lives shaped by inertia rather than intention, societies can drift into informational environments shaped by reflex rather than reflection. In both cases, recovery requires not merely more data or a better strategy, but a reorientation of attention.

If attention is the mechanism by which we choose what matters, then the erosion of attention (individually or collectively) is a threat not just to knowledge, but to agency itself.

Why an Oracle Won’t Save Us

Confronted with infinite information, a tempting solution is to build an AI that sorts it for us: an intellectual oracle that declares what’s true, what’s false, and what deserves our attention.

This approach contains profound risks.

Any oracle must be trained on data, shaped by human choices, constrained by political forces, and embedded in institutional structures. There is no apolitical oracle. There is no neutral filter. Every mechanism that determines what is true also determines what is permitted.

Such systems become targets for capture. The more powerful the oracle, the greater the incentive to manipulate it. History offers numerous examples: church authorities policing orthodoxy, states controlling the media, and platforms shaping algorithmic visibility. A machine oracle merely centralizes this vulnerability.

And if humans outsource judgment to machines, our capacity for judgment atrophies. The prefrontal cortex, like any muscle, deteriorates with disuse. The widespread adoption of digital contact storage offers a small but instructive example: the capacity to memorize phone numbers, once routine, has atrophied within a generation.

An oracle doesn’t strengthen human cognition. It replaces it. And what is replaced is lost.

The Path Forward: Augmented Human Intelligence

The alternative isn’t artificial general intelligence as oracle. It’s Augmented Human Intelligence (AHI): systems designed not to replace human judgment but to strengthen it.

The crisis we face isn’t a deficit of intelligence. Humans reason well when given time, clarity, and context. The crisis is a deficit of attention: the resource required to use that intelligence.

AHI treats attention as the scarcest and most valuable cognitive resource. It provides context, identifies manipulation, surfaces what matters, and widens rather than narrows our informational horizons.

Where AGI aims for autonomy (an artificial mind operating independently), AHI aims for partnership: systems that amplify human insight while keeping us at the center of decision-making.

Consider tools that:

- Summarize not just what sources say, but where they diverge

- Flag when you’re operating within a narrowing informational corridor

- Highlight when emotional triggers are high and analytical engagement is low

- Translate across communities of belief, making one group’s assumptions legible to another

None of these declares what is true. All preserve the integrity of human judgment while strengthening it.

In a world of infinite language, the most valuable technology is one that helps humans reclaim the ability to choose what deserves attention.

The Stakes

Language built our civilizations. It gave us laws, markets, stories, institutions, and meaning. But language alone didn’t make us human. What made us human was the ability to attend: to choose what deserves focus, to reflect before acting, to imagine before building.

If the breakthrough of artificial intelligence was the realization that “attention is all you need,” perhaps the breakthrough of our time will be the realization that attention is all we have.

Democracies depend on citizens who can understand one another. Markets require reliable information. Scientific progress depends on distinguishing truth from fiction. When language becomes infinite, and attention becomes scarce, these premises weaken.

We must not mistake polarization for pluralism. Pluralism assumes a shared foundation of facts. Polarization emerges when that foundation collapses.

AHI isn’t a luxury. It’s a necessity.

What’s Next

Next week, I’ll explore the path from imagination to understanding. Because the real challenge isn’t just building smarter AI. It’s building AI wisely.

And wisdom, as it turns out, requires something scaling can never provide: feedback.

Notes & Further Reading

The entire argument, including a framework for evaluating information systems and detailed AHI design principles, appears in my white paper, The Attention Crisis: Language, Meaning, and the Architecture of Augmented Human Intelligence.

The three-layer model of reality comes from Yuval Noah Harari’s Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind.

The neurobiological foundations draw on Robert Sapolsky’s Behave: The Biology of Humans at Our Best and Worst.

The UN’s findings on Facebook’s role in Myanmar appear in the Report of the Independent International Fact-Finding Mission on Myanmar (2018).

Token volume estimates are derived from publicly available data on global text production. See the whitepaper appendix for methodology.