Beyond Scale: Architecture as the Real Path to Intelligence

Lessons from Evolution for a Smarter Kind of AI

A medical AI reviews a chest X-ray and flags a suspicious shadow. The radiologist asks, “Why did you highlight this area?”

The system responds: “Abnormality detected, confidence 0.87.”

That’s not an answer. That’s a probability.

What the radiologist actually needs is reasoning: Did you see calcification patterns? Does this match pneumonia cases from your training data? Or is this just that imaging artifact we keep seeing from the new equipment?

The system can’t answer because it doesn’t think in modules. Perception isn’t separate from memory, which isn’t separate from causal reasoning. It has parameters. Billions of them, all entangled in ways even their creators can’t untangle.

After 18 months of studying how evolution built intelligence, here’s what I’ve come to understand: this isn’t a limitation of scale. It’s a limitation of architecture.

The Scaling Paradox

For years, the race toward artificial intelligence has been defined by scale: bigger models, more data, ever more powerful GPUs. Each generation promises a leap toward general intelligence. Yet as the systems grow, their adaptability, reasoning, and efficiency remain stubbornly limited. Energy use grows exponentially while real understanding stays flat.

Which raises an obvious question: if intelligence were just about scale, wouldn’t we be there by now?

Evolution found a different path. It achieved intelligence not by building a larger brain, but by discovering a smarter architecture. The biological brain is not a single processor that scaled up over time. It’s a network of specialized systems, each optimized for a different purpose, all coordinated by a dynamic executive function.

This orchestration, not sheer size, is what made intelligence adaptive.

And here’s what keeps me up at night: we’re racing ahead with our silicon brains while ignoring an older truth that evolution already solved.

Lessons from the Biological Processing Unit

Four billion years of evolution serve as a masterclass in constrained design. The human brain consumes about 20 watts of power (less than a light bulb), yet it learns continuously, recovers from errors, and remains remarkably flexible.

Evolution’s secret was architectural, not computational.

It discovered four enduring principles that define adaptive intelligence:

Executive Orchestration: A dynamic coordination layer, the prefrontal cortex, that routes attention, integrates inputs, and balances speed with reflection. Think of it as a conductor who knows which sections of the orchestra to bring forward at different moments.

Continuous Plasticity: Learning that never stops, with mechanisms for remembering, forgetting, and adapting in real time. Your motor cortex refines a tennis serve over weeks while your prefrontal cortex updates its model of a colleague’s reliability based on a single conversation. Different modules, different timescales, all learning simultaneously.

Architectural Bias Correction: Built-in checks that detect and compensate for the shortcuts and blind spots of intuition. This is what Daniel Kahneman describes: System 1 thinks fast, System 2 thinks slow, and the prefrontal cortex decides when to override instinct with deliberation.

Integrated Value Alignment: Ethical reasoning and trade-off awareness embedded at the core, not added later as guardrails. The brain doesn’t process decisions and then check them against values. Values shape the processing itself.

Each of these principles isn’t just a metaphor for intelligence. It’s an engineering strategy. They explain how to achieve adaptability without constant retraining, transparency without regression, and value alignment without afterthought.

These same principles can guide the next generation of artificial systems. Instead of scaling a single monolithic network, we can design orchestrated, modular architectures that evolve with experience and context.

The question is: will we?

The Human Architecture of Intelligence

Here’s what I find most striking about the brain’s design: it’s not a hierarchy of commands. It’s a federation of specialized systems. Vision, language, memory, emotion, each performing a distinct function. Intelligence emerges not from any one part, but from how they work together.

Think about how you navigate a busy intersection:

- Your visual system tracks vehicles, pedestrians, and traffic signals

- Your memory system recalls traffic rules and past experiences

- Your prediction system models where that cyclist is heading

- Your emotional system flags the approaching ambulance as urgent

- Your motor system prepares your foot to brake or accelerate

- Your executive function weighs all these inputs and decides when to cross

This happens in milliseconds. But it’s not a single calculation. It’s a coordinated symphony of specialized modules, each contributing its expertise.

The prefrontal cortex acts as executive orchestrator, allocating attention and deciding when to rely on instinct and when to slow down and reason deliberately. This isn’t a top-down dictatorship. It’s learned coordination, adapting based on experience and context.

Where humans are limited by fatigue and bias, machines could complement us by recognizing when to switch modes. An AI architecture that understands these human dynamics could serve as a cognitive partner rather than a replacement. It would amplify judgment, not automate it.

This is a confederated architecture: a system in which intelligence emerges from the orchestration of specialized models, rather than a single massive model.

Language, Causality, and Abstraction

Language is more than a communication tool. It’s humanity’s first true invention, a shared framework for reasoning about what does not yet exist.

Judea Pearl describes this as the “ladder of causation”: from seeing, to doing, to imagining what could have been.

Current AI models excel at the first rung. They’re remarkably good at seeing patterns in data. But they struggle with the higher rungs. Understanding how interventions change outcomes (doing) and reasoning about counterfactuals (imagining) remain largely out of reach.

A truly intelligent system must climb this ladder, linking perception to intervention to “what if” reasoning.

Language isn’t just for describing things; it’s the tool we use to build new ideas. It creates a space where thoughts can meet, clash, and grow into something more complex.

This is what current monolithic models miss. They can generate language, but they don’t yet think in language the way we do. They can’t use it to model causation, to imagine alternatives, to reason about things that haven’t happened yet.

Toward Modular and Adaptive AI

So what would a biologically-inspired architecture actually look like?

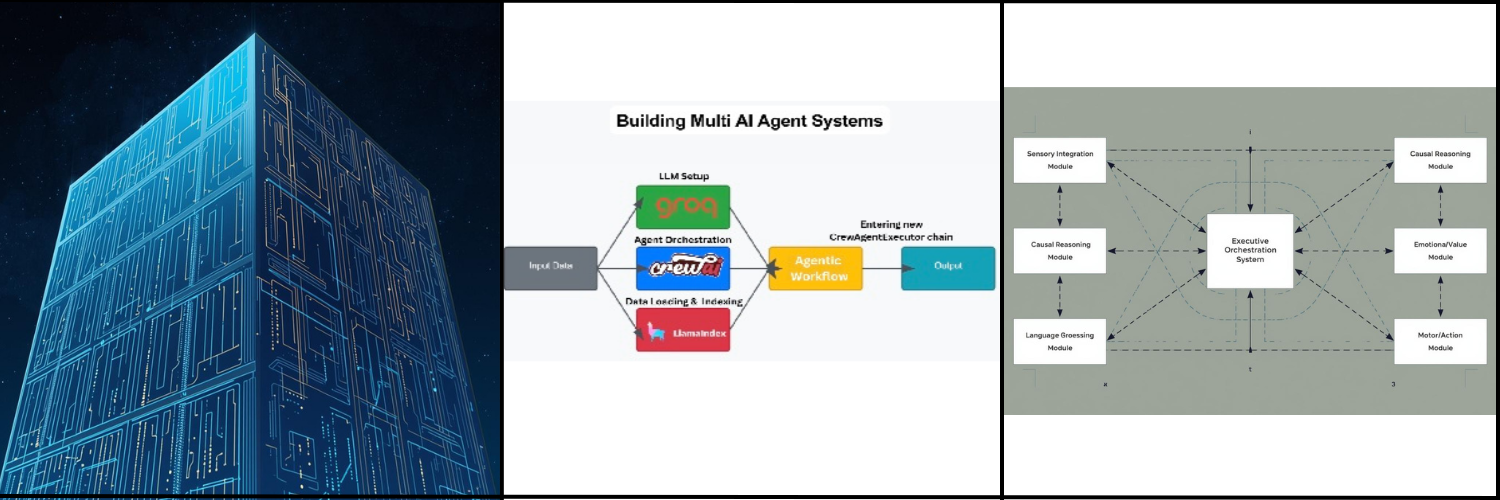

Imagine a community of specialized systems coordinated by an executive layer that learns which modules to trust for which problems. Not one vast model, but a confederated system.

Each module contributes unique strengths:

Perception modules handle sensory input and context: vision, language, audio. Optimized for pattern recognition, just like your visual cortex.

Memory modules store and retrieve both episodic experiences (what happened) and semantic knowledge (what things mean). Some memories persist for years, others fade in minutes.

Causal reasoning modules explore why events occur and what would change outcomes. This is where the system climbs Pearl’s ladder, moving beyond correlation to actually model cause and effect.

Value assessment modules weigh ethical trade-offs and uncertainty. Not trained implicitly through data, but explicitly programmed with principles that can be inspected and debated.

The executive orchestrator sits at the center, allocating attention, integrating results, and updating its strategy through feedback. It doesn’t process information itself. It coordinates those who do.

This modular design solves three persistent problems in today’s large models: opacity (because decisions can be traced through modules), fragility (because learning happens locally, not globally), and inefficiency (because the system allocates compute only where it’s needed).

Continuous plasticity ensures the system learns from each experience without forgetting past lessons. Bias correction mechanisms monitor performance and recalibrate when overconfidence or drift appears.

This design replaces brittle retraining cycles with ongoing adaptation. Intelligence that evolves rather than resets.

Can We Build This Today?

Not completely. But we can start.

Phase 1 is modular decomposition. We separate current models into specialized components and build simple orchestrators that route queries. Proof of concept: a medical AI with distinct diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment modules that can explain which module contributed to which part of its recommendation.

Phase 2 is adaptive orchestration. We enable the coordinator to learn from experience, allowing it to discover and refine superior coordination strategies over time.

Phase 3 is causal grounding, and it’s the hard part. Integrating true causal inference frameworks so the system can answer “what if” questions by modeling causation, not just retrieving similar examples.

Phase 4 is ongoing value alignment. We make ethical frameworks explicit, inspectable, and improvable through human oversight.

This isn’t science fiction. The research directions are clear. The question is whether we’ll invest in architecture as much as we’ve invested in scale.

From Scale to Wisdom

Scaling will consistently deliver more output, but not necessarily more insight. Architecture is what turns power into purpose.

Evolution proved that intelligence emerged from constraint, not abundance. The brain achieves more with twenty watts than our largest models do with megawatts, not through brute force, but through smart design.

The lesson for AI is the same: smarter coordination, not more compute.

This is why the goal shouldn’t be artificial general intelligence in isolation. It should be augmented human intelligence (AHI), systems that extend our perception, challenge our assumptions, and help us see the world more clearly.

The difference matters.

AGI aims for autonomy, or, to put it another way, the creation of an artificial mind that can operate independently of us.

AHI, by contrast, aims for partnership, in which systems are designed to amplify human insight, reasoning, and ethical judgment while keeping us at the center of decision-making.

A confederated architecture naturally supports this partnership. The orchestrator can flag uncertainty, request human input, and explain its reasoning in terms humans can understand and override.

This isn’t settling for less capable AI. It’s building AI that’s more capable precisely because it’s designed to complement human judgment rather than replace it.

Why This Matters Now

We’re at an inflection point. The scaling paradigm shows diminishing returns. Each new generation requires exponentially more resources for incrementally better performance.

Meanwhile, AI energy consumption threatens to overwhelm power grids. Training GPT-4 used roughly 50 GWh. At current growth rates, AI could consume 10% of global electricity by 2030.

The modular approach offers a path out: efficiency through specialization, sustainability through targeted updates, transparency through explainable reasoning, and alignment through explicit values.

But perhaps most importantly, modular architectures acknowledge that intelligence isn’t a single thing to be achieved through brute force. It’s an emergent property of well-designed systems working together.

Evolution’s great lesson isn’t scale; it’s emergence: intelligence born of specialization, coordination, and feedback.

That’s the lesson evolution spent four billion years teaching us.

The question is whether we’re listening.

What’s Next

We’ve talked about what to build: modular architectures inspired by evolution’s four-billion-year R&D project.

But there’s a deeper question underneath all of this: how do we know what to build?

How do we move from wonder at what’s possible to wisdom about what matters? How do we follow curiosity without getting lost in the seduction of pure computation?

Next week, I’ll explore the path from imagination to understanding. Because the real challenge isn’t just building smarter AI. It’s building AI wisely.

And wisdom, as it turns out, requires something scaling can never provide: feedback.

Notes & Further Reading

For a more complete technical architecture and phased development roadmap, see my research paper Beyond Scale: Towards Biologically Inspired Modular Architectures for Adaptive AI.

The foundational argument about why scaling alone won’t work appears in my research paper Attention Is All We Have: What AI’s Greatest Breakthrough Can Teach Up About Being Human.

Judea Pearl’s “ladder of causation” is detailed in his book The Book of Why: The New Science of Cause and Effect.

Daniel Kahneman’s System 1/System 2 framework comes from Thinking, Fast and Slow.

For Gary Marcus’s critique of the scaling paradigm, see Rebooting AI: Building Artificial Intelligence We Can Trust.