Brain-Computer Interfaces

Could They Be the Path to True Cognitive Augmentation?

We’ve all felt it: that snap judgment, the unscrutinized gut feeling. A hiring manager feels an instant affinity for a candidate from their alma mater. A doctor dismisses a patient’s nagging symptom as stress. This isn’t a failure of character; it’s a feature of our biology. Our brains, for the sake of efficiency, are wired for swift, often flawed, System 1 shortcuts.

The Core Problem

This is the core problem my work on Augmented Human Intelligence (AHI) aims to solve. The goal is not to outsource our thinking to an artificial mind, but to build systems that enhance our own cognition in real-time. Imagine a partner that doesn’t think for you, but ensures you’re thinking well by mitigating biased reflexes and scaffolding deliberate, System 2 reasoning when it matters most.

But here’s the rub: our current AI tools are architecturally unsuited for this intimate task. Today’s large language models are like brilliant critics shouting suggestions from another room. They’re disconnected from the real-time, subconscious flow of our thoughts where bias takes root. The clumsy I/O of keyboards and speech creates a bandwidth bottleneck far too narrow for a meaningful cognitive partnership.

The architecture is wrong.

So what would the right architecture look like? And could emerging brain-computer interface technology point us toward an answer worth exploring?

The Vision: Real-Time Cognitive Scaffolding

Let’s return to our hiring manager and imagine what true cognitive augmentation might look like.

As she feels that unconscious affinity for the familiar candidate, a sophisticated system—somehow reading the aggregate neural signatures associated with automatic judgment—could detect this moment of System 1 processing.

It would not override her. That would be the antithesis of augmentation. Instead, it would provide cognitive scaffolding:

- Gently highlighting the other candidate’s superior relevant experience on the digital resume in front of her

- Posing a silent, Socratic prompt: “Have you sufficiently weighed Factor X?”

- Triggering a subtle state of focused alertness encouraging a moment of deliberate reflection

The human remains the decider. But she is no longer deciding with a flawed, unaided toolkit. She’s now equipped with a real-time support system to construct sounder judgment.

This is the architecture of attention, made tangible. It’s not about AI thinking for you—it’s about providing the scaffolding to ensure you are thinking, clearly and deliberately, when it matters most.

The question is: what would it take, architecturally, to make this possible?

The Current State of Brain-Computer Interfaces

While this vision might sound like science fiction, the foundational technology is advancing faster than most people realize. Multiple companies are now implanting devices in human brains—not in distant labs, but in actual patients going about their daily lives.

Neuralink: The High-Bandwidth Approach

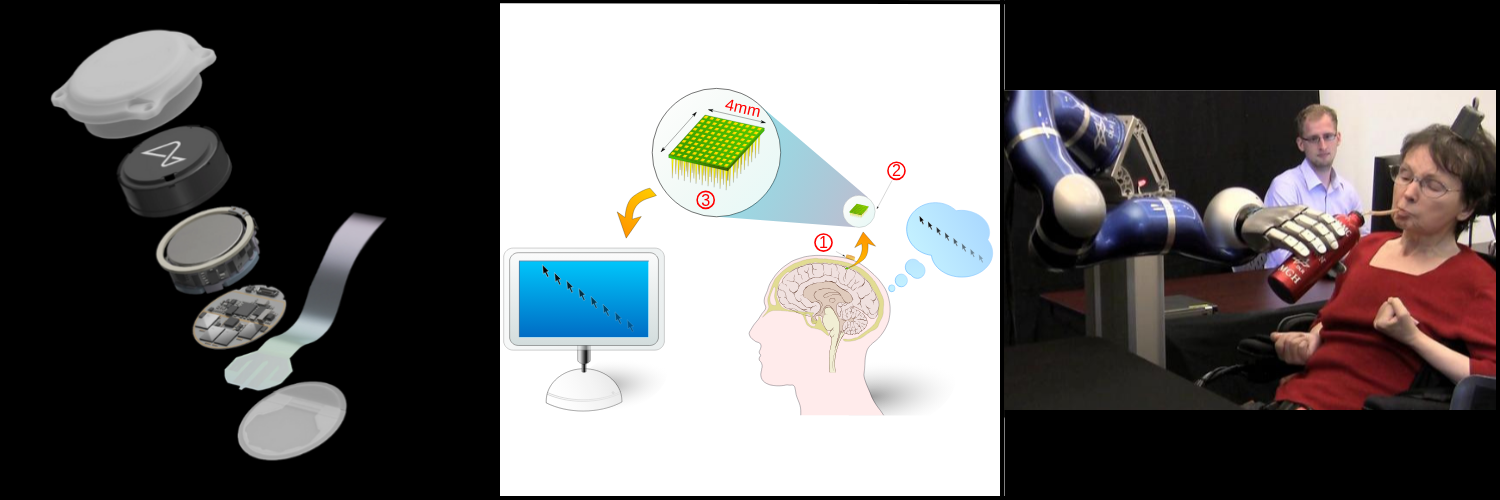

Neuralink, Elon Musk’s neurotechnology company, represents the most prominent effort in invasive BCIs. By mid-2025, nine people had received the company’s N1 implant, which consists of ultra-thin electrode threads inserted directly into the motor cortex through precisely drilled holes in the skull.

What can they do? The results are remarkable for patients with severe paralysis:

- Noland Arbaugh, the first recipient (paralyzed from a diving accident), can play video games like Civilization VI, browse the web, and control his computer entirely through thought

- Bradford Smith, who has ALS and can no longer speak, used his implant to edit YouTube videos and restored his voice using AI trained on pre-ALS recordings of his speech

- Another participant uses the device to operate computer-aided design software, creating 3D objects with his mind

The device uses 1,024 electrodes across 64 threads to capture neural signals with high resolution. Neuralink has raised over $1.3 billion in funding, including a $650 million Series E round in mid-2025, and plans to expand trials significantly. They’re also developing “Blindsight,” a device to restore vision by stimulating the visual cortex, which received FDA Breakthrough Device designation.

Synchron: The Minimally Invasive Alternative

While Neuralink captures headlines, Synchron has taken a radically different approach that could prove more scalable. Their Stentrode device is inserted through the jugular vein, like a stent, and positioned in a blood vessel above the motor cortex. No open brain surgery required.

The trade-off? Lower bandwidth. Synchron’s device provides basic “switch” control—think clicks and scrolling—rather than the high-resolution signal capture of cortical implants. But this simplicity has advantages:

- Six patients in their COMMAND study showed zero serious adverse events over 12 months

- The median deployment time is just 20 minutes

- Patients can control their devices “on day one” without extensive training

- The device works with Apple products via Switch Control, including iPhone, iPad, and Vision Pro

Synchron just raised $200 million (November 2025), bringing total funding to $345 million. They’re preparing for pivotal trials in 2026 and moving toward commercialization.

The Broader Landscape

Three other companies are pushing the boundaries in different directions:

Blackrock Neurotech (Salt Lake City) has the most human experience with dozens of implants since 2004 through academic research trials. Their Utah Array is the workhorse of BCI research, and their MoveAgain device received FDA Breakthrough Designation.

Precision Neuroscience (founded by a former Neuralink executive) is developing an ultra-thin, flexible “Layer 7” electrode array that sits on the brain’s surface like a piece of tape, inserted through a minimal incision. They achieved record-setting 4,096-electrode human recordings.

Paradromics (Austin) is building a high-bandwidth implant specifically for speech restoration. They completed their first human recording during epilepsy surgery in June 2025.

Industry investment has exploded: $2.3 billion flowed into BCI technology in 2024 alone, more than triple the 2022 level.

The Architectural Case for BCIs

So why would a brain-computer interface be relevant to cognitive augmentation in the context of the hiring manager scenario?

The answer lies in bandwidth and latency.

Current AI interactions require:

- Conscious awareness of a need for assistance

- Explicit formulation of a query

- Physical input (typing/speaking)

- Waiting for processing

- Reading/hearing the response

- Conscious integration of that information

By the time our hiring manager has noticed her bias, consciously decided to seek help, typed a question into ChatGPT, and read the response, the critical moment has passed. The automatic judgment has already been made.

A true cognitive augmentation system would need to:

- Detect the neural signatures of automatic, System 1 processing in real-time

- Intervene at the moment of decision, not after

- Communicate through high-bandwidth, low-latency channels that don’t require conscious attention

- Preserve human agency, scaffolding rather than replacing judgment

This is an architecture problem. And BCIs represent the only technology category that could theoretically provide this level of intimate, real-time integration.

Why This Path May Be More Tractable Than AGI

Here’s where the argument gets interesting.

The dominant narrative in AI is the race toward Artificial General Intelligence—an external, autonomous entity that may ultimately operate beyond our control. This pursuit is fraught with profound alignment challenges: How do we ensure a superintelligent system’s goals remain aligned with an entire species when we can barely agree among ourselves?

An AHI system enabled by BCI is architected for alignment by default. Its core purpose is to serve the goals and judgment of its individual human user. The human’s values are the system’s compass. There’s no separate entity with separate goals to align.

Yes, BCIs come with serious challenges:

- Safety: Surgical risks, long-term biocompatibility, signal stability

- Privacy: Neural data is perhaps the most intimate information imaginable

- Security: Protection against hacking or unauthorized access

- Equity: Ensuring technology doesn’t create cognitive “haves” and “have-nots”

- Regulation: How do we govern devices that sit at the intersection of medical device, consumer technology, and fundamental human capabilities?

But critically, these are engineering and governance challenges—problems of building secure systems, designing reversible controls, and crafting sensible policy. These are the kinds of problems we have centuries of collective experience solving, even if the stakes here are uniquely high.

The Honest Limitations

Let’s be clear about what BCIs cannot do today and may not be able to do for years or decades:

Current capabilities are limited: Today’s devices can control cursors, select menu items, and type—all amazing for people with paralysis, but nowhere near the real-time cognitive intervention we’ve been discussing. The hiring manager scenario remains firmly in the realm of speculation.

Signal quality matters: The brain is noisy. Distinguishing the neural signature of “automatic bias” from “deliberate consideration” or “fatigue” or “hunger” is an unsolved problem. We’re still mapping these patterns.

The “read” problem: All current BCIs are focused on output—translating brain signals into actions. Effective cognitive scaffolding would also require input—the ability to communicate suggestions back into conscious awareness in a way that feels natural rather than intrusive. This bidirectional communication at the cognitive level remains largely theoretical.

Long-term unknowns: We don’t yet know the effects of living with a brain implant for 20, 30, or 40 years. Will the brain adapt? Will signal quality degrade? Will there be psychological effects?

The consumer value question: For medical applications (restoring movement, communication, or vision), the value proposition is obvious. But would a healthy person undergo neurosurgery for a 10% productivity boost? The practical value of potential consumer applications hasn’t been established.

These limitations are real and significant. Anyone promising near-term cognitive augmentation via BCI is selling science fiction, not science.

The Question Worth Asking

So why write about this?

Because the question itself matters: What architectural approach gives us the best shot at building AI systems that genuinely augment rather than replace human judgment?

Current AI development is racing toward autonomous systems that think for us. The AHI vision asks: what if we instead built systems that help us think better?

Brain-computer interfaces represent one possible path toward that vision—perhaps the only path that could provide the bandwidth, latency, and intimacy required for real-time cognitive partnership. The technology is advancing rapidly, the investment is real, and the early results are promising.

But it’s also early. Very early.

The medical applications are already life-changing for people with paralysis or neurological conditions. The cognitive augmentation vision? That’s still a thought experiment backed by emerging technology rather than a near-term product roadmap.

Perhaps that’s exactly when we should be having this conversation—before the technology is fully realized, while we still have time to think carefully about whether this is a path worth pursuing, and if so, how to pursue it responsibly.

Your Turn

What’s your gut reaction to the idea of a brain-computer interface for cognitive augmentation?

Would you consider it for yourself if the safety profile was proven? What applications would be worth it? What makes you hesitate?

I’m curious where your thinking leads.

Sources and Further Reading

- MIT Technology Review coverage of Neuralink, Synchron, and other BCI companies (2024-2025)

- Government Accountability Office report on Brain-Computer Interfaces (GAO-25-106952)

- Clinical trial data from COMMAND study (Synchron) and PRIME study (Neuralink)

- Industry funding data from NeuroFounders and venture capital analyses

What’s Next

Next week, we take the architectural principles we’ve been exploring and apply them to the most personal domain: our own lives. If intelligence emerges from modular orchestration rather than raw power, what does that mean for how we structure attention, goals, and growth? The answer leads to a framework for deliberate living.